Our Grandparents Survived so We Could Thrive. We Need to Protect that Space.

By AJ Siegel, 3GDC President

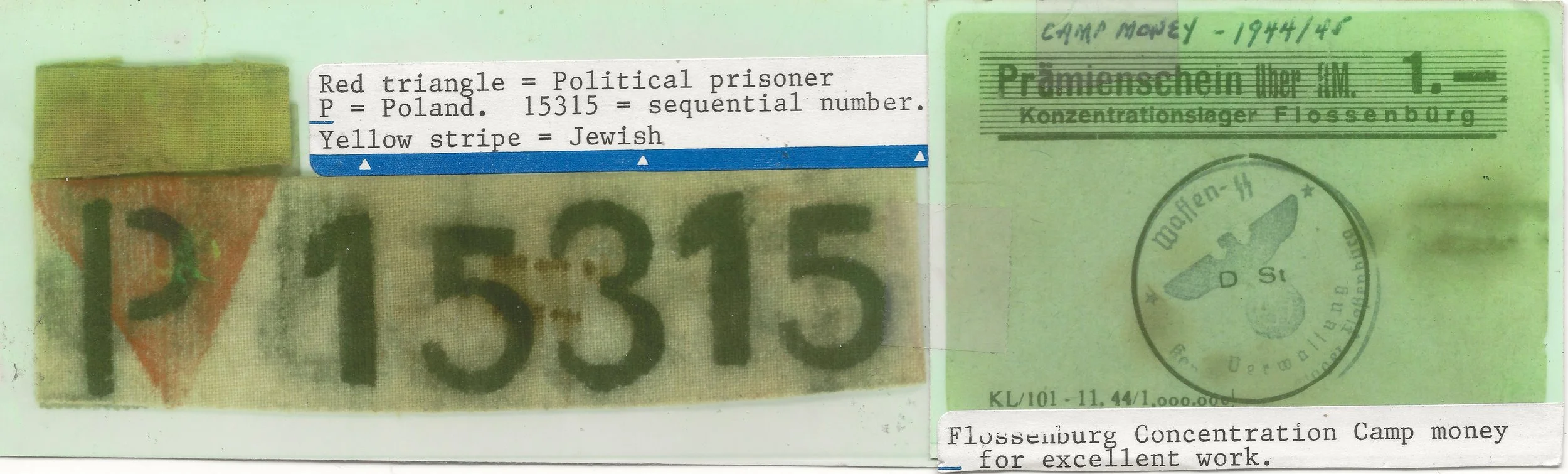

Top-left: My grandfather’s Flossenberg Concentration Camp number; top-right: money he received for excellent work.

My grandfather was present in my life until I was 27. I was always learning he was a Holocaust survivor and what that meant. He spoke to my middle school, high school, and college. I once drove him up to Albany to speak at my sister’s school. It’s been an ever-present part of my life.

My grandfather was born in Poland, in 1925 in a town called Gorlice that had about 8,000 people. At the time about half was Jewish. Their lineage went all the way back to the founding. He went to public school, Hebrew school, and bible school.. He kept kosher and observed the sabbath.

An image of my grandfather taken in Frankfurt in 1945

He was 14 when Germany invaded Poland. The Nazis made a ghetto in his town. My grandfather was put to work digging ditches. The synagogue was destroyed and turned into a horse stable. One day he came back from work and his family was gone–executed or removed, he’d never find out. What was maybe the hardest part of all, his Polish neighbors turned on him, and the indifference and outright Jew hatred he faced was terrible.

As the tide of the war was turning, the Nazis brought a lot of Jews into Germany to hide them and keep them working. He was moved west to a camp (Flossenburg) some 500 miles away. There was a point along that train that they stopped at Auschwitz, and he overheard a debate between the military logistics organization that wanted these prisoners to work, and the SS that wanted to kill them. The military person was more convincing, so they got back on the train. He likely escaped the fate of gas chambers.

In 1945, as the Russians were closing in, the Nazis started marching them toward big cities. He escaped and eventually found American soldiers. He spent less than a year in Germany in a displaced persons camp, before being connected with the remaining parts of his family in Connecticut. He got a job, learned English, met my grandmother in the early 50s, and together they had my mom and my uncle.

He lived in Connecticut the rest of his life. He became a paralegal at a law firm started by another survivor he met on the boat to America. He started speaking in the 1970s and never stopped. For 40 years, half his life was telling his story.

I was always very involved with Jewish life. It often meant getting my grandfather to tell his story.

Often my school papers were about the Holocaust–my grandfather had all the books, so I didn’t have to go to the library.

After my grandfather was diagnosed with cancer, it occurred to me that he was not immortal. That someone had to keep this story going. It took another 8 years, but after my daughter was born, I began telling his story.

Telling survivor stories is a tool that can combat antisemitism. It shows the danger of other-ing others. There is a duty or responsibility as a descendant of a survivor. That burden often can scare people away. Our grandparents survived so we could thrive. We need to protect that space.

I was really fortunate to have all four of my grandparents in my life. They were so present and absolutely shaped who I am. So much of me is my grandfather. He helped make me the man I am. He was so proud to be American and have citizenship and be able to thrive and create a family. We exist, because he survived, and we need to make the most of our lives. That drives me.

We’ll teach you how to share your grandparent’s story.